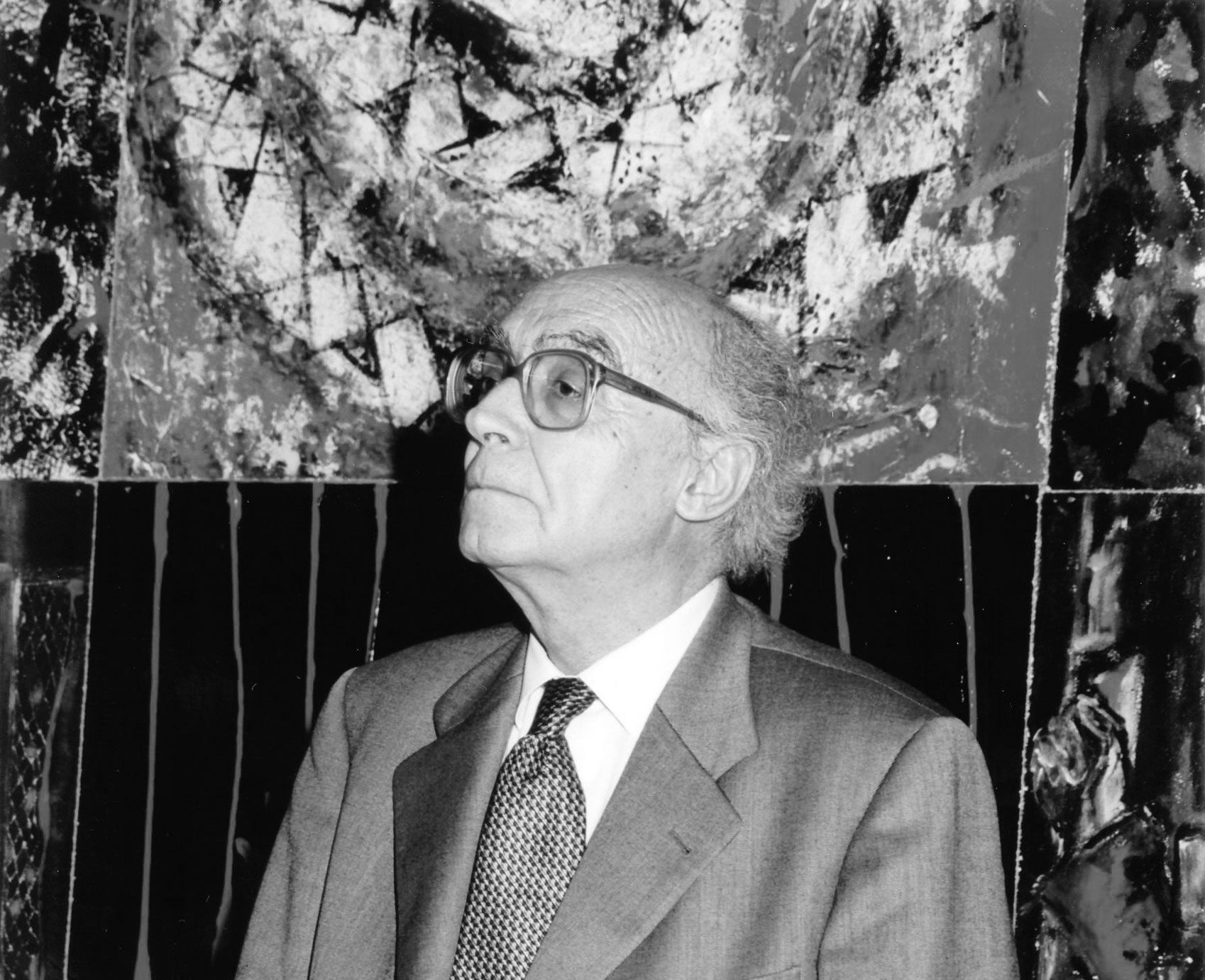

Biography of the Author

José Saramago was born into a poor rural family in the village of Azinhaga in the province of Ribatejo on 16th November 1922, although his date of birth was officially recorded as the eighteenth and the family moved to Lisbon before his second birthday. He grew up there although during his childhood he spent the holidays with his grandparents back in his village of birth. In Lisbon, he attended secondary school, high school and a vocational college but due to financial difficulties he was unable to finish the course.

He got his first job as a metalworker, after which he worked in various professions, as a designer, social security clerk, translator, editor, and journalist. He published his first book, a novel entitled ‘Terra do Pecado’ in 1947, which was out of print for many years until a second edition came out in 1966.

For twelve years, he worked for a publishing house, where he was literary editor and also worked on the technical side. He wrote literary reviews for the review ‘Seara Nova’. From 1972 to 1973, he was on the editorial staff of the newspaper ‘Diário de Lisboa’, where he was a political commentator, and was also responsible for producing the cultural supplement, for about a year. From April to November 1975 he was deputy editor of the newspaper Diário de Notícias. From 1976, he supported himself by writing, first as a translator and then as an author.

He was a member of the first board of directors of the Associação Portuguesa de Escritores – Portuguese Writers Association – and from 1985 to 1994, and president of the general assembly of the Sociedade Portuguesa de Autores – Portuguese Authors’ Society.

Saramago married Pilar del Río in 1988, and from 1993 divided his time between Lisbon and the island of Lanzarote in the Canaries, in Spain, in both of which places he had houses. In 1998 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

José Saramago passed away on 18th June 2010. (Fundação José Saramago).

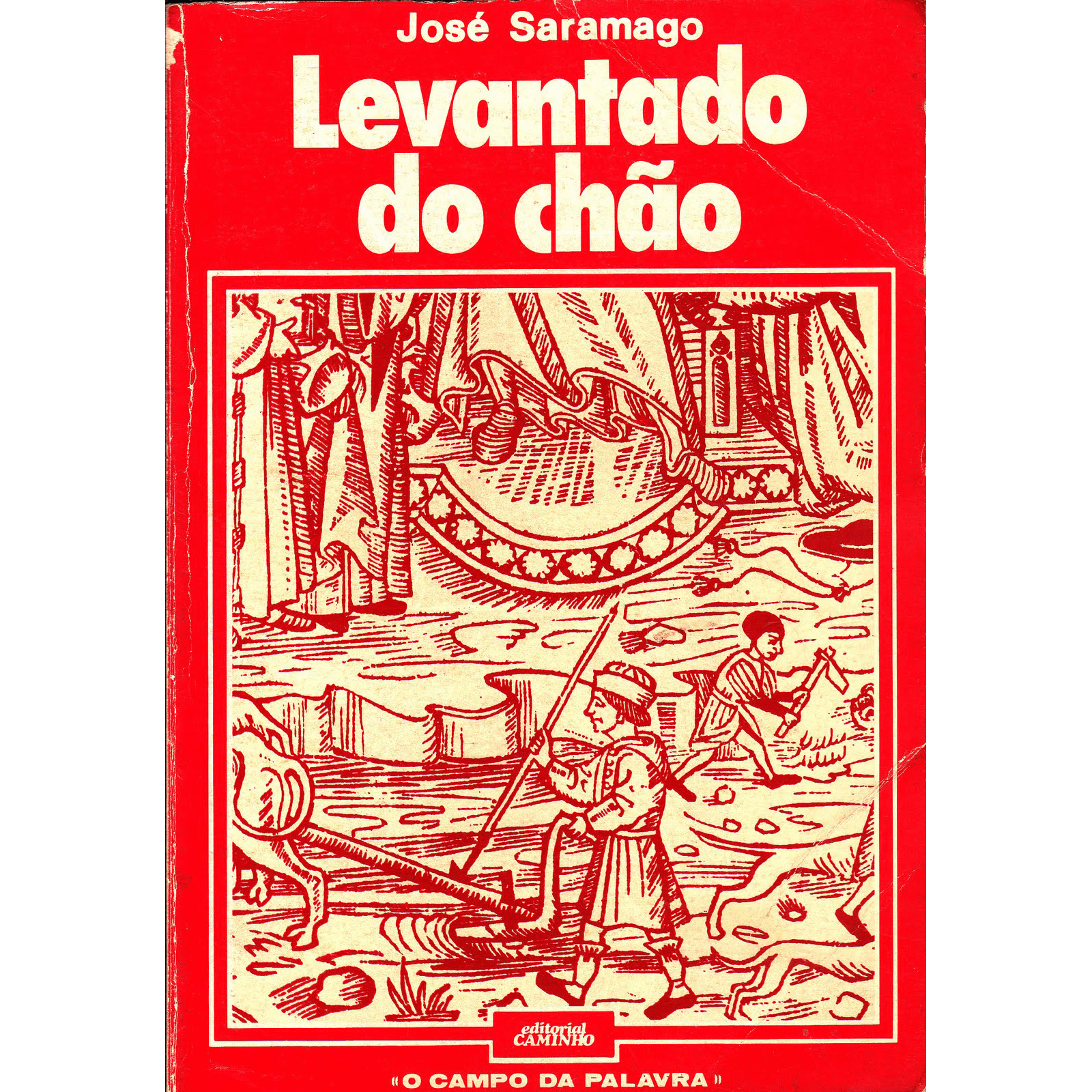

Raised from the Ground – the historical context

Raised from the Ground is set in the 20th century. The early years of the century were marked by the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the First Republic, on 5th October 1910, which brought the Portuguese people the hope of a society founded on the 19th-century French revolutionary ideology of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”. Soon the general economic crisis, a consequence of the First World War, and the strong climate of social unrest, as well as internal conflict in many countries, gradually destroyed the plans of the new republic, which succumbed to the military coup of 28th May 1926 and the establishment of a fascist dictatorship in Portugal. With the introduction a new constitution in 1933, the Estado Novo – New State – was established, which proved to be one of the longest fascist dictatorship regimes in the history of the Western world, lasting more than four decades and ending only on 25th April 1974 with the Revolution of Flowers.

The reader is able to follow all these important events in Raised from the Ground from the perspective of the history of the struggle for survival of three generations of the “Mau-Tempo” family. They are from “Monte Lavre”, which the author makes clear is a reference to the town of Lavre, a parish in the municipality of Montemor-o-Novo. The “Mau-Tempos” belong to the socioeconomic group known as the proletariat of farm-workers, which for centuries had constituted the majority of the active population of the Alentejo region. As the author describes, “João Mau-Tempo” is “The first-born with no first-born’s legacy, the owner of nothing at all, he casts a very brief shadow.” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, p. 47). He belongs to the class of those dispossessed of land and capital, forced to sell their physical strength and resist in order to survive, unlike the situation in the North and Centre of the country, where the majority of the population owned or rented small plots of land, The Alentejo has always been characterised by the existence of large agrarian estates, or latifundia, on which the majority of the population was forced to work for a few landowners. The exploitation of the people is evident in the book: there is the example the account of the wages of “Joaquim Carranca”, paid in kind plus a small amount of money and the even lower wages paid to the young “João Mau-Tempo”, which provides an instance of the widespread child exploitation (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, pp. 64-5). Up until the 1940s, model of the exploitation of child labour along with payment in kind was generally found on large estates in the region, and a working day of 17 to 18 hours was common up until the 1960s (cf. Fonseca, 1994, pp. 33-34).

Landowners used the existence of the fascist regime to impose conditions on working people and use repressive force against them if necessary by legal means in order to ensure they did not complain or react and keep wages low. According to Teresa Fonseca, they inherited “a centuries-old posture of arrogance in their dealings with the rural proletariat, imposed on them endless working hours and miserable wages and inflicted inhumane and humiliating treatment on them, all with impunity. According to José Claudino Tregeira, they acted as if they owned the poor and servants, like feudal lords, and they “had no scruples in forcing young women workers and girls to serve as maids in their own homes, later discarding them and their children “to their sad fate” (Fonseca, 2018, p.49). In her work, the writer collected reports from rural workers that show what kind of spirit existed among the rural workers and highlights their generous community spirit, without which the story of the working class would be even more tragic (cf. Fonseca, 2018, p.53). António Gervásio, a communist leader, recalls an episode when some workers dared to seek employment and food from a farmer in Montemor-o-Novo and his comment was “If they’re hungry, let them eat straw.”. To this the workers responded, a few days later, by holding up a sign which read: “As long as there is meat, we won’t eat straw!” (Gervásio, 2013, p.20). The unfavourable socioeconomic context in which rural workers in the Alentejo lived and worked is the main cause of the social protests and major events in the struggle for better conditions that are recorded in history. For example, there is the campaign for an eight-hour working day, which was achieved in 1962.

Supporting large rural landowners against the workers was the Salazar regime and its mechanisms of repression. The dictator deprived the working class of knowledge and freedom itself: “The biggest and most decisive weapon is ignorance.” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, p. 71), with hunger as the predominant factor: “The people were made to be dirty and hungry” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, p. 72), out of fear of bloodthirsty repression by PIDE, the International and State Defence Police, “made simply in order to beat the people.” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, p. 72), which stifled any sign of opposition to the regime.

Poverty and repression are two elements that clearly demonstrate the harsh history of 20th-century Alentejo social system. However, Raised from the Ground, as the title indicates, is the story of the struggle for justice in the face of capitalist exploitation and that of the revolutionary and resistance against the fascist regime that raised the Alentejo agricultural proletariat from the ground to the “unique and new-risen day” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, p. 387), the day on which the latifundia were occupied, the day of the Agrarian Reform “the most beautiful achievement of April”, with “a thousand living and a hundred thousand dead, or two million sighs rising up from the ground” (Raised from the Ground, Saramago, 2018, pp. 385-386).

In addition to the historical context of the work, from the turn of the century and the early 20th century to the Revolution of Flowers, Raised from the Ground also makes reference to a previous era with the introduction of the dead and legends as well as clear references to the town’s historical past. There is the use of the character “Lamberto Horques”, whose historical antecedent is the German Lamberte Orques, to whom King John I gave Lavar on 17th July 1430, with a view to populating and cultivating the local area (cf. Fonseca, 2014, p. 12). The heritage of these bygone times is evident in the blue eyes of “João Mau-Tempo”, a possible genetic trait deriving from his German ancestry. The wider temporal scope of the work raises the issue of the collective identity of societies in the Alentejo, whose culture over the centuries was bound up with resistance. Witness, for example, the change from cereal farming to livestock farming in the 18th century, which led to the expulsion of many working families from the land, turning them into the unemployed beggars who lived in a state of miserable poverty. Most were dependent on seasonal work, going hungry for the rest of the year, and being forced to beg and steal to survive. The lack of work was also due to the absentee landowners only being occasionally forced by decree to employ a few workers. At the same time, the law prohibited working people from using olives or coal as fuel and collecting firewood to heat their homes and there were severe punishments for those who disobeyed.

This is why the Alentejo agricultural proletariat, as historian Teresa Fonseca has found, has a tradition of labour struggles that spans the centuries (cf. Fonseca, 2005).

The socioeconomic situation of the feudal era led to the early formation of class consciousness among the Alentejo rural proletariat; however, it was only in the 1930s that the rural proletariat across the country began to be organised. The action of the Portuguese Communist Party led to the politicisation and increased social awareness of the Alentejo rural proletariat. From then on there were many struggles and demands put forward by anti-fascists in the municipality of Montemor-o-Novo.

The strong revolutionary spirit of these people, which José Saramago succeeded in portraying so well, assigns the people of Montemor-o-Novo a leading role in the history of resistance to various forms of oppression and exploitation of man by man across the centuries.

Author Bibliography – Novels

Terra do Pecado, 1947

Manual de Pintura e Caligrafía, 1977

O Ano da Morte de Ricardo Reis, 1984

O Evangelho Segundo Jesus Cristo, 1991

Ensaio Sobre a Cegueira, 1995

Todos os Nomes, 1997

A Caverna, 2000

O Homem Duplicado, 2002

Ensaio Sobre a Lucidez, 2004

As Intermitências da Morte, 2005

A Viagem do Elefante, 2008

Caim, 2009

Claraboia, 2011

Alabardas, Alabardas, Espingardas, Espingardas, 2014